B.C. cider makers blend tradition and innovation

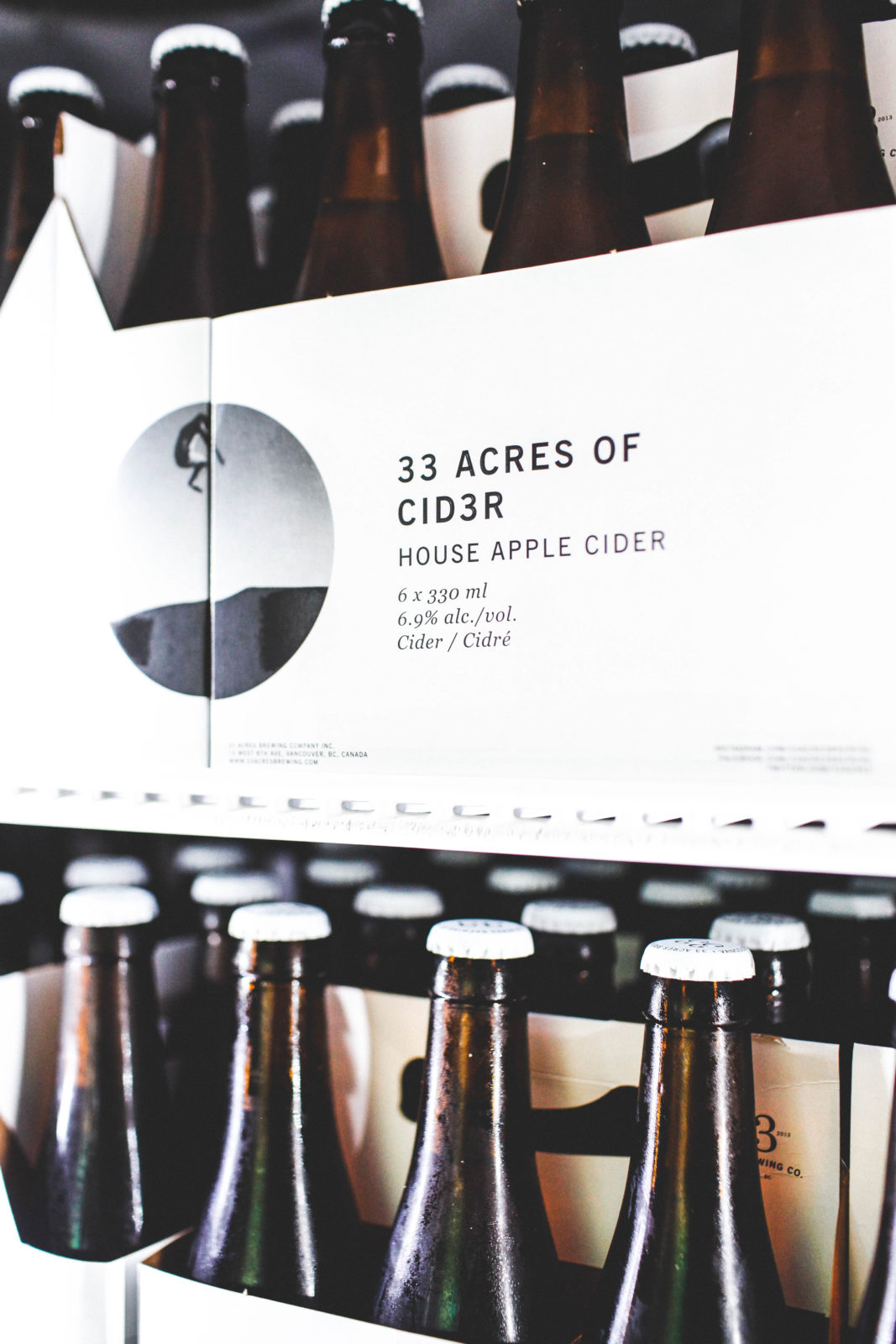

You could be forgiven for thinking of cider and beer as two sides of the same coin. After all, most of the time they’re close to each other in colour and alcohol content, and you drink them in the same kinds of social settings. They are sold close to each other in the liquor store, and they’re both made in gleaming tanks by cool, craft-focused people. It’s tempting to think that, at the end of the day, cider is basically the same as beer, except it’s gluten-free and made from apples.

But it’s those apples that make all the difference. If you’re a small-scale brewer in B.C., you have access to malt and hops from all over the world through an efficient supply chain of processors and distributors, and all that stands between you and a batch of Czech-style pilsner or UK-style bitter is some ingenuity and time. B.C.’s small-scale cider makers, though, are one step closer to the soil, thanks to the province’s liquor licensing regulations. In order to avoid paying a staggering 73% markup to the BC Liquor Distribution Branch, a cidery must own an orchard at least two acres in area, and source at least a quarter of the fruit it ferments from that orchard or from orchard land that the cidery leases. And whether it comes from the cidery’s own orchard or not, all of the fruit it ferments must come from within the province. So, while only a few of B.C.’s small brewers are also barley farmers, many of its cider makers are also orchardists.

While the orchard requirement may seem restrictive, this has actually allowed many unique cideries to flourish here. For Janet Docherty, owner of Merridale Cidery & Distillery in Cobble Hill, maintaining a 20-acre orchard allows her to keep a supply of the unique apples that can be used to make Old World-inspired ciders. “Our varieties originally come from England, France, Germany, though predominantly from England,” she explained. “Here, we have a climate that mirrors those [European] conditions. It’s perfect for the growth of the cider apples.”

Just as wine grapes differ from the table grapes one finds in supermarkets, true cider apples stand apart from their commercially available cousins, often known as “eating apples.” Many lack the storage qualities and aesthetic appeal that make an apple variety commercially viable, but possess other characteristics that endear them to cider makers, such as being high in sugar, acid, or tannins. Varieties high in tannins—which contribute complexity to a cider in the form of bitterness or astringency—tend to be the most prized and sought after, even if Dabinett, Kingston Black, and Yarlington Mill are hardly household names. For Docherty, there is no substitute for cider apples in her Old World-inspired ciders. “Eating apples,” she says, “don’t give you body.”

Merridale is in the enviable position of having a reliable supply of cider apples, having planted its Vancouver Island orchard over three decades ago, and also having recently acquired a second orchard in the Okanagan. Most of B.C.’s other small-scale cider makers, though, are newer to the game and grow smaller orchards. And while eating apples can easily be purchased in bulk, cider apples remain elusive on the open market.

Kristen Trovato, owner of Okanagan Mobile Juicing, wishes this weren’t the case. “I’ve talked to quite a few growers and tried to convince them to plant cider apples,” she said. “But—nope. They don’t see the value in it.” Cider apple varieties, explained Trovato, often produce biennially, with one year’s bumper crop followed by a minimal harvest in the next, leading orchardists to plant more reliable producers to ensure a regular harvest.

Apples in general, Trovato said, are falling out of favour with many farmers due to the relatively low prices paid to apple growers by the large fruit-packing houses. “I see people ripping out orchards all the time and planting the next cash crop—cherries, grapes. And it makes me very sad.” Growing apples for cider, Trovato believes, is one of the only ways to make an orchard profitable. While the more esoteric, cider-specific apple varieties are nearly impossible to find in bulk in the province, Trovato said that she sees opportunities for cideries and growers to work together to ensure a supply. “For a grower, as long as they have a committed buyer for a variety that’s really good for cider, they might have some luck.”

While the Old World cider apple varieties may be the most coveted, some B.C. cider makers are learning to appreciate the nuances of the fruit that is closer at hand. Not long before starting Pender Island’s Twin Island Cider, co-owners and co-cidermakers Katie Selbee and Matthew Vasilev travelled to Herefordshire, in the UK’s cider-making heartland, for inspiration. While the

experience left them with a genuine appreciation for the bittersweet apples at the heart of traditional British cider, opening a cidery on the other side of the world made them open to another way of seeing things.

“The heirloom varieties here,” said Selbee, “are pretty different than the traditional English cider varieties. They’re much higher acid. You get more of a white wine profile from these apples than the tannic body of the English style.”

Selbee celebrates this distinction. “I’m so much happier with the cider we’re making out of the apples here,” she said. “We’re open to how you can make a good cider out of what is at hand.”

While the orchard Selbee and Vasilev planted on Twin Island’s own property is small and has just begun producing, the two have agreements with landowners around Pender Island to maintain and harvest a number of backyard orchards. This provides them with access to unique apple varieties that, while not specifically recognized as cider apples, bring unique flavours and aromas to their products. It has also allowed them to operate entirely without purchasing fruit from large conventional orchards where labour is sometimes provided by insecurely-employed temporary foreign workers. For Selbee, sourcing fruit from the Gulf Islands reflects a broader commitment to environmental and social justice.

“We got into this for more than just making cider,” she said. “We wanted to step outside of the system of commercial and industrial farming.”

The craft beer world continues to grow and diversify, and sometimes it seems like its growth is limited only by brewers’ creativity and customers’ willingness to try new flavours. But the growth of cider in BC is on a slower trajectory, dependent on cider makers’ ability to grow and source good fruit from within the province. True cider apples can make great cider, if you can find them. But cider makers are a creative lot. It may be that the right apples for making a great cider are the apples that you have.