The Growler has put together this simple guide to wild fermenting cider in the hopes of inspiring a few of you to give it a try.

Hint: by using wild fermentation, it’s easier than you think.

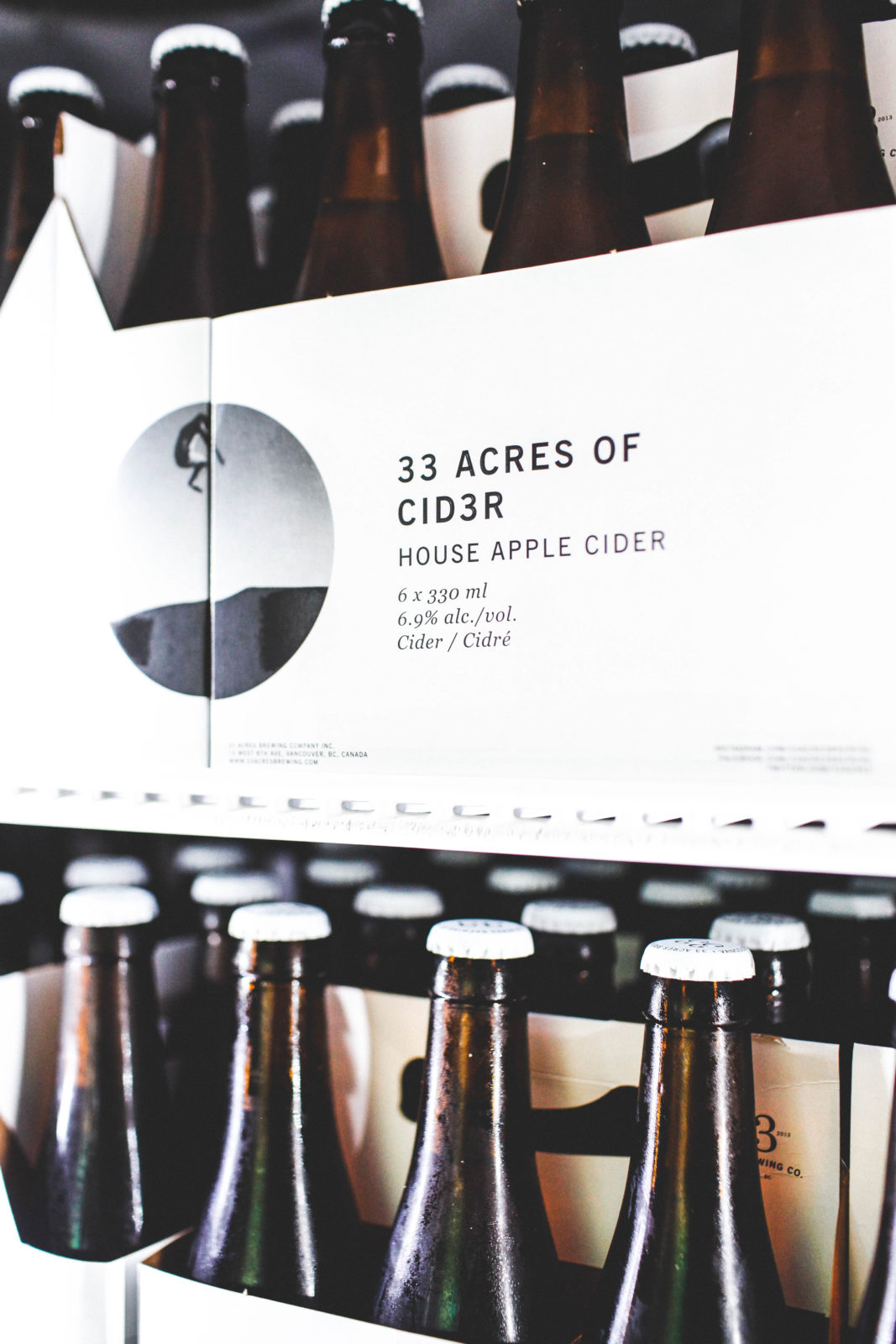

Sure, there are plenty of refreshing, delicious, B.C. ciders to choose from, but why not try your hand at making it yourself? It doesn’t get any more “craft” than that.

First, you press some apple juice. Next, you sterilize it somehow. If it were a beer wort, you’d boil it, but it’s juice and you don’t want it to taste cooked, so you add sulfites. Now you’re ready to rehydrate your yeast and add it per the manufacturer’s instructions. Not so simple, right?

But what if you skip every step except the first? What if you press the juice and then you just—wait? If that’s what you do, you’ve entered the world of wild fermentation. And, as it turns out, there are quite a few B.C.’s cider makers here already. In some ways, it’s a remarkably simple process.

“I don’t do anything,” explains Alyssa Hubert, cider maker at Penticton’s Creek & Gully Cider, who says after she adds a minimal dose of potassium metabisulfite, used by nearly all cider makers to control spoilage bacteria, “the juice just goes into whatever vessel I’m putting it in and I wait for the yeast to wake up and start eating the sugar.”

For a few days the juice is quiet. But then something happens.

“About twenty-four hours before the fermentation really kicks,” said Hubert, “you can actually see the yeast culture. You can see a foam on the top of the cider, and it’s a really good sign—the yeast are healthy and they’re starting to breed.”

And there’s nothing subtle about it, she says, adding: “You can hear the yeast.”

According to Claude Jolicoeur, author of The Complete Cider Maker’s Handbook, after apple juice is pressed, wild yeasts present on the skin and flesh will begin to ferment the juice within a few days of pressing, so long as the temperature is at least 10°C. A diversity of microflora is involved in this process, from the “apiculate” yeasts that appear at the beginning of the fermentation, but cease to work once the alcohol content climbs north of four per cent, to wild strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae—the stuff we typically use to make almost all beer and wine—that take over afterward.

All of this might sound a little daring and, well, it should. Wild fermentation represents a kind of radical trust the microorganisms that a cider maker likes will out-compete the ones they don’t.

But for some cider makers, wild fermentation yields results so reliable they use it exclusively. Hubert is one. So is Mike Harris, of Summerland’s Dominion Cider. Five years ago, about twenty percent of Dominion’s output was fermented with wild yeasts, and Harris used cultured yeasts for the remainder. But three years ago, says Harris, we said ‘let’s go for it,’ and since then all of Dominion’s ciders have been made with wild yeast. If there are drawbacks, for Harris, they’re minor and logistical in nature.

“One of the challenges for us,” he says, “is that wild ferments take longer.”

As opposed to cultured yeasts that can ferment a cider to completion in a week or less, Dominion’s wild-fermented ciders can take four-to-six-weeks to reach dryness—the point at which all of the juice’s sugar has been converted to alcohol. “We had to buy some extra vessels to hold all the cider,” he notes.

But the advantages outweigh the drawbacks and, for both Harris and Hubert, a key advantage is that using wild fermentation helps to draw complexity from apples that were bred to be eaten, not drank. Proper “cider apples”—often particularly high in tannin and sugar—are difficult to find in B.C., and most cider makers use more readily available table apples for the bulk of their production.

The slow speed and microbial diversity of wild fermentation helps to add complexity to the flavour of the cider, which can highlight the under-appreciated nuances of humble, everyday apples. “Spartans have this cool, very silky-smooth caramel quality about them,” says Hubert.

And you don’t have to go all in. Some cider makers use wild fermentation as just one of a number of approaches to cider production. For Clinton MacDougall, cider maker at Gibsons’ Sunday Cider, wild fermentation’s role is to express the hidden characteristics of his most unique cider-specific apples, as well as the specific microbiological personality of his cidery.

“We have our own house microbial terroir at Sunday Cider,” explains MacDougall, describing the aromas produced during wild fermentation with an array of descriptors including “banana cream pie” and “orange creamsicle.” After the first surge of fermentation is through, these notes mellow and cohere over months of resting in barrels and bottles. Eventually, the subtleties of the apples themselves begin to shine through, alongside hints of the notes produced in fermentation.

“It’s for that broad array of characteristics,” said MacDougall, “that we use wild fermentation.”

So, if you have some apples and you want to make cider with them, go ahead and press them into juice. And, if you’re not in a hurry, you might want to think about just walking away at this point. Be patient. Let the wild yeast do its work and see what comes of it. Maybe it feels a bit risky, but you’re in good company.

Required drinking: Try these wild-fermented B.C. ciders

Creek & Gully Cider // Flora

Dominion Cider // First Principles

Sunday Cider // Sunday Wild