Ever since beer has been brewed, women have played an important role in brewing.

Beer has long been thought of as a man’s drink. Growing up in the 1980s, I recall a Budweiser ad featuring three “Bud girls” lying on a towel, with “Budweiser: King of Beers” spelled out across the torsos of their swimsuits. The message was clear: girls were decoration and beer was for the guys. The stats are slowly changing, but beer drinkers remain predominantly male, and beer branding – both craft and corporate – often embodies “masculine” values. In other words, the modern beer industry has forgotten the vital importance of women in brewing.

Archaeological records of brewing stretch back 6000 years, and much of the earliest artistic and documentary evidence of it (from approx. 2100 BCE) links beer with women. The Epic of Gilgamesh, one of the earliest written stories, features the tale of a wild man, Enkidu, who is brought into civilization by a woman named Shamhat who insists that he learn how to drink beer (and he does—a lot!). Even in this very early story, beer is already associated not only with being human, but with female power.

Around the same time, The Hymn to Ninkasi honoured the Sumerian goddess of beer. This famous poem is essentially a recipe for beer, and one that was recreated thousands of years later by Anchor Brewing in 1989. But Ninkasi is far from the only goddess associated with beer; other Sumerian and Egyptian beer goddesses are Siris, Siduri, Tenenet, and Nisaba, and Sekhmet, whose wrath was mitigated by her beer consumption. She awoke not with a hangover, but as the gentle Hathor. The goddess Mut received beer tributes from wealthy and revered Egyptian head brewer Khonso Im-Heb and his wife (c. 1000 BCE).

These ancient cultures associated beer with women, who were often tasked with baking and its cousin, brewing. Artwork depicts women not only brewing, but also drinking and even engaging in sexual behavior while drinking. The earliest legal text, the Code of Hammurabi (ruler of Babylon, 1792-1750 BCE) has laws governing the behavior of tavern-owners – always referred to as female. Women had control over brewing, even in these early patriarchal cultures.

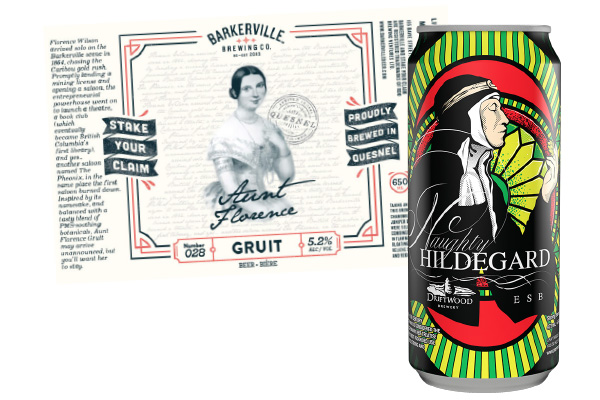

While the Greeks and then the Romans preferred wine over beer, brewing nevertheless flourished over the centuries, particularly in areas of Europe that didn’t benefit from the Mediterranean’s warmer weather. After the Roman empire’s collapse, women were still closely associated with brewing. Since Christianity was sweeping over Europe in the early medieval period, there were no longer gods and goddesses blessing the beer—but there were saints. Brigid, an early medieval Irish saint, miraculously produced beer out of her bathwater, and an early medieval poem depicts her imagining heaven as a great ale-feast—a beer-drinking party, with God, Christ, the angels, and the saints partaking of a “lake” of ale. The twelfth-century German abbess Hildegard of Bingen, canonized later as a saint, famously was one of the first writers to recommend the use of hops in beer (which Victoria’s Driftwood Brewery celebrates in its Naughty Hildegard ESB).

Because monasteries brewed beer throughout the Middle Ages, we often think of monks when imagining beer’s history. However, while monks were brewing for a larger consumer base and scaling up production using their substantial financial resources, home brewers kept up a small but steady beer supply for their own households and neighbourhoods. The majority of this was done by female “brewsters.” Women’s skill in brewing even sometimes enabled them to become aletasters, who enforced brewing standards, or to be a court witness if a woman was charged with selling faulty beer.

Between 1300 and 1600, brewing in Western Europe changed dramatically for women. Brewsters were gradually excluded from beer’s profitability and those who continued to brew either publicly or privately were often mocked. But why this shift? For one, the devastation of the Black Death from 1346-1348 caused grain prices to decrease, which increased ale consumption and allowed beer production to be scaled up (if one had the resources). In addition, civic brewing guilds increased across Europe, which contributed to the increasing standardization and regulation of brewing (Bavaria’s 1516 Reinheitsgebot, the beer purity law, is one example). Finally, the increased use of hops enabled beer to be stored longer and shipped greater distances, which supported the increasingly industrialized brewing profession. Brewing as an industry was becoming larger and more expensive. Men had the access to money and guild membership, and the ability to draw up business contracts—but women often had none of these privileges (only widows, for example, had the legal right to create a contract). In one example from a town in Essex, 100 percent of the 21 ale-sellers and brewers were female in 1464, but by 1500 there was only one woman among the 15 brewers in town.

In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, beer was popular and alehouses were raucous “nurseries of naughtiness,” according to William Lambarde. Women who sold or made beer were objects of suspicion. John Skelton’s poem “The Tunnyng of Elynor Rummyng,” about a disgusting alewife who corrupts other women with her brews, is a famous example of anti-alewife literature. Brewing illegally could land you in jail, which is what happened to Mary Arnold, who was sent to London’s notorious Fleet Prison in 1639 for brewing in her home. Women were certainly drinking beer—Queen Elizabeth I had beer throughout the day—but producing it was no longer women’s work. It had become a profitable—and public—industry, and thus belonged to men.

The popularity of distilled spirits during the Industrial Revolution turned beer into a drink of moderation rather than drunkenness. Beer, therefore, was ripe for increased production using newly available technologies. England’s classic styles, such as porters, bitters, and India pale ales, were created during this time, but women had little involvement in the industry. Across the Atlantic, North American settlers rejected English beer in favour of American beer as an act of political resistance, and by the late nineteenth century there were over 4,000 breweries in the United States (40,000 in Europe). With the industry booming, where were the women? For the most part, they were brewing at home, without recognition or reward—with a few exceptions. Martha Jefferson became well known for her brewing, which was accomplished, of course, through the unrecognized labour of enslaved people, but many other women brewed in private, as they had centuries earlier.

The beer industry slowed to a crawl during Prohibition and the temperance movements of the early twentieth century. When alcohol became legal again in North America, the only breweries left were the largest ones (such as Pabst, Coors, and Anheuser-Busch), all dominated by men. In the UK, the Institute of Brewing had just three female members until 1945, although more women worked in brewing laboratories and marketing after World War II. By the 1970s, however, women entered the workforce in greater numbers than ever before and made their mark on the emerging craft beer scene. For example, while Jack McAuliffe is credited as the founder of the first American craft brewery, New Albion, it was only with the help of his partners Jane Zimmerman and Suzy Denison that he funded the brewery and made the beer. The same can likely be said for many of the craft breweries that have opened here in British Columbia.

Supplied photos

Now, in 2020, women constitute a growing segment of the craft beer industry, and advocacy groups such as the Pink Boots Society support women’s education and participation in brewing. I would love to see more breweries creating beers that honour both women’s role in the history of brewing, and brewing’s history as “women’s work.” Women have an important role in the future of craft beer, but they are also the forgotten element of its past.

Sources and further reading:

Baron, Stanley Wade. Brewed in America: the History of Beer and Ale in the United States. Little, Brown, 1962.

Bennett, Judith M. Ale, Beer and Brewsters in England: Women’s Work in a Changing World, 1300-1600. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996.

Cornell, Martyn. Beer: The Story of the Pint: The History of Britain’s Most Popular Drink. Headline Book Pub Ltd, 2004.

Damerow, Peter. “Sumerian Beer: The Origins of Brewing Technology in Ancient Mesopotamia.” Cuneiform Digital Library Journal 2012:002 (2012).

Hornsey, Ian Spencer. A History of Beer and Brewing. Cambridge: Royal Society of Chemistry, 2003.

Martin, A. Lynn. Alcohol, Sex, and Gender in Late Medieval and Early Modern Europe. London: Palgrave MacMillan, 2001.

Nelson, Max. The Barbarian’s Beverage: A History of Beer in Ancient Europe. Windsor: University of Windsor, 2005.

Ogle, Mary. Ambitious Brew: The Story of American Beer. Wilmington: Mariner Books, 2007.

Perry, David. “What Google Bros Have in Common with Medieval Beer Bros.” Pacific Standard, August 22, 2017.

Unger, Richard. Beer in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004.